Concours Mondial de Bruxelles has decided to organise its 25th competition in Beijing, China, thus giving participating producers an opportunity to approach one of the most dynamic wine markets in the world.

The rapid growth in China’s vineyard acreage has taken the global wine industry by surprise in recent years. However, according to professor Demei Li, associate professor of wine tasting and oenology at the Beijing Agricultural College, China is first and foremost a consumer country offering huge potential for exporters.

Concours Mondial de Bruxelles supports producers entering the competitive Chinese wine market by finalizing deals with local importers and retailers. JD.com, China’s largest online retailer and its biggest overall retailer with 266.3 m active customers annually, has already agreed to include awarded wines from Concours Mondial de Bruxelles on its e-commerce platform. Medal-winning wines from the competition are already available on the shelves of JD’s offline fresh food supermarket, 7Fresh.

CHINESE WINE CONSUMPTION

According to OIV, China was the 5th largest global “consumer” of wine in 2016 with per capita consumption continuing to rise. Analyst Euromonitor estimates that wine consumption in China grew 5.3 percent by volume in 2016 from 2015, whilst alcoholic drinks fell 3 percent in the same period. In 2020 China is expected to consume 94 million cases, up from 52.7 million cases in 2016, equating to growth of 79%[1].

The way the Chinese drink wine is changing too. A report by Goldman Sachs and Gao Hua Securities[2] found that elderly drinkers in China are traditionalists, opting for white spirits (baijiu), while young people prefer western wine. The report also predicts that, “as the older generation lives longer, and as people’s health awareness increases, more wine will be consumed in China.” The market may expand as the millennial population grows older.

Chuan Zhou of Wine Intelligence believes that the future of wine consumption in China lies in the younger female population, who account for 50% of the nation’s imported wine drinkers. Chinese women drink wine for health-related reasons and for the way it makes them feel: very refined and successful.

CHINA – THE 5thLARGEST IMPORTER OF WINE WORLDWIDE

According to OIV, China is the 5th largest global importer of wine in terms of volume, and the 4th largest importer by value. Chinese domestic demand is “the biggest contributory factor to trade growth”. By the year 2020, imported wine is expected to grow to 50% of the Chinese wine market.

The Chinese Association for Imports and Exports of Wine and Spirits predicts that China is “tipped to become the world’s second biggest importer of wine by 2020”, overtaking more traditional markets like France and the UK – with imports estimated to be worth a staggering $21.7billion[3].

In 2017, 746 million litres of bulk and bottled wine worth close to 2.8 billion USD were imported into China. The numbers reflect a 16.9% increase in volume and 18% increase in value compared to the previous year. The volume of imported wines to China has doubled since 2013 (from 377 million litres).

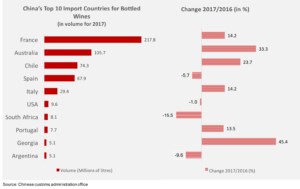

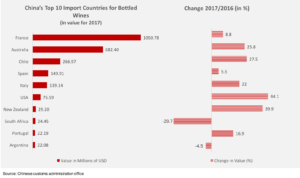

France still leads the way in the Chinese import market, holding over 40 % of market share. And although Bordeaux reds remain China’s favourite wines, other regions such as Languedoc and the Rhone Valley are gaining recognition with better value offers.

Australia is the second largest source for imported wines in China, accounting for more than 20% of market share. Its Shiraz-based wines are among consumers’ favourites. Imports of Australian wines increased by 33% in volume and 25.8 % in value compared to 2016. Australia also benefits from the bilateral trade agreement signed in 2015.

Chile, similarly, benefits from lower import tariffs for its wines, leading to a rise of 23.7% for its exports to China.

The highest increase among the top 10 wine importer countries to China with +45% by volume was posted by Georgia. The surge proves that China is not only interested in the major producer countries, but is starting to witness a shift in demand towards wines from other regions. China and Georgia signed a Free Trade Agreement in May 2017 which will gradually see the removal of all import tariffs on Georgian wines to China.

In value terms, the United States posted impressive growth of 44% for its wines imported by China despite the slight decrease in import volume. The average price for wines from the US was 7.85 USD per litre, which ranked the country second after New Zealand, whose average bottled wine price remains the highest among all competitors (10.68 USD/litre). Although imports of Spanish wine grew in value by 5.5 % in 2017, Spain still holds the lowest import price of 2.21 USD/litre.

Italy has increased its presence in China in recent years, hosting its international trade fair Vinitaly in China. In 2017, the country witnessed a 22 % percent increase in value and 14.2 % increase in volume.

Although they didn’t make it into the top 10, Bulgarian wines performed remarkably well with 130 % growth in value in 2017 over the previous year.

Sparkling wine imports showed a 27.2% increase in their average price per litre, pointing to increased demand for quality. By 2020 China’s sparkling wine imports are expected to grow by 43.6% to 2.19 million cases compared with 1.53 million cases in 2015.

TACKLING THE CHINESE WINE MARKET

According to Demei Li, associate professor of wine tasting and oenology at the Beijing Agricultural College, precision marketing is the key to success in China.

Countries like Australia for example have shown awareness of issues affecting Chinese consumer trends. These include major regional differences across the country – in terms of food, religion and social activities for example – making national coverage impossible. Linguistic issues are also involved, making it essential to choose the right interpreter and a Chinese brand name.

From a food perspective, salient flavour profiles dictate style preferences and there is no such thing as a unified Chinese palate: The North is more geared to salty foods, the North-West to spicy dishes, the South prefers even spicier foods and the South-East sweet, whilst the coastal areas, predictably, opt for seafood.

External factors such as price, packaging, region, variety/style and taste are also of paramount importance and style descriptors on packaging – for example dry red wine – are an important way of reaching out to consumers.

Probably one of the most important lessons to be learnt is that European standards cannot be transposed to China, although the appeal of genuine quality is a common denominator. Professor Li stresses that history and technical details are meaningless to the Chinese but that authenticity is essential; bespoke products specifically targeting the Chinese are doomed to failure because they imply lower standards. But perhaps one of the most important rules to remember is that foreign exporters are not competing with local wine producers, but with home-grown drinks such as baijiu.

[1]The IWSR Vinexpo Report 2011-2021

[2]Quoted by the South China Morning Post:http://www.scmp.com/business/commodities/article/2105607/chinas-wine-consumption-growing-tandem-ageing-millennials

[3]http://www.cwsa.org/china-wine-market/